Countering this, other commentators argued that rising oil prices would stimulate the discovery and enhanced recovery of conventional oil, the development of ‘non-conventional’ resources such as oil sands, and the diffusion of substitutes such as biofuels and electric vehicles, without economic disruption. This process was forecast to lead to substantial and sustained disruption of the global economy, with alternative sources of energy being unable to ‘fill the gap’ at acceptable cost on the time scale required. During the first decade of this century, an increasing number of commentators began forecasting a near-term peak and subsequent terminal decline in the global production of conventional oil-so-called ‘peak oil’. Oil is a finite and rapidly depleting fossil resource, and the capacity to maintain and grow supply has been a recurrent concern for over 50 years. Nonetheless, despite heavy taxation in most countries and historically high global oil prices, a litre of diesel remains cheaper than a cup of coffee. One litre of diesel contains enough energy to move a 40 tonne truck three kilometres-a feat that would be impossible with battery-electric propulsion for example.

Our familiarity with oil can obstruct recognition of how remarkable a substance it is: oil took millions of years to form from the remains of marine and other organisms it is only found in a limited number of locations where a specific combination of geological conditions coincide it possesses an unequalled combination of high energy per unit mass and per unit volume and it is both highly flexible and easily transportable.

Oil accounts for more than one third of global primary energy supply and more than 95% of transport energy use-a critically important sector where there are no easy substitutes. The aim is to introduce the subject to non-specialist readers and provide a basis for the subsequent papers in this Theme Issue.Ībundant supplies of cheap natural liquid fuels form the foundation of modern industrial economies, and at present the vast majority of these fuels are obtained from so-called ‘conventional’ oil. These include: the origin, nature and classification of oil resources the trends in oil production and discoveries the typical production profiles of oil fields, basins and producing regions the mechanisms underlying those profiles the extent of depletion of conventional oil the risk of an approaching peak in global production and the potential of various mitigation options. This paper summarizes the main concepts, terms, issues and evidence that are necessary to understand the ‘peak oil’ debate. Few debates are more important, more contentious, more wide-ranging or more confused.

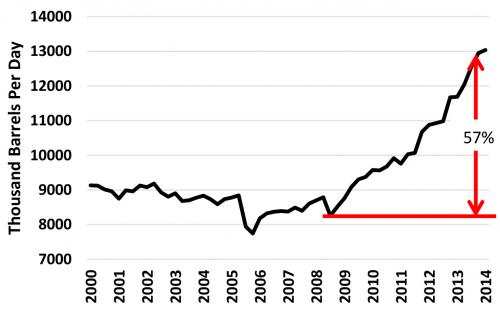

There are disagreements over the size, cost and recoverability of different resources, the technical and economic potential of different technologies, the contribution of different factors to market trends and the economic implications of reduced supply. Some commentators forecast a peak in the near future and a subsequent terminal decline in global oil production, while others highlight the recent growth in ‘tight oil’ production and the scope for developing unconventional resources. Abundant supplies of oil form the foundation of modern industrial economies, but the capacity to maintain and grow global supply is attracting increasing concern.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)